- Biodesign Academy

- Posts

- Who Is Really Working in the Lab?

Who Is Really Working in the Lab?

Yuning Chen on labour, ethics, and the hidden ecologies of biodesign

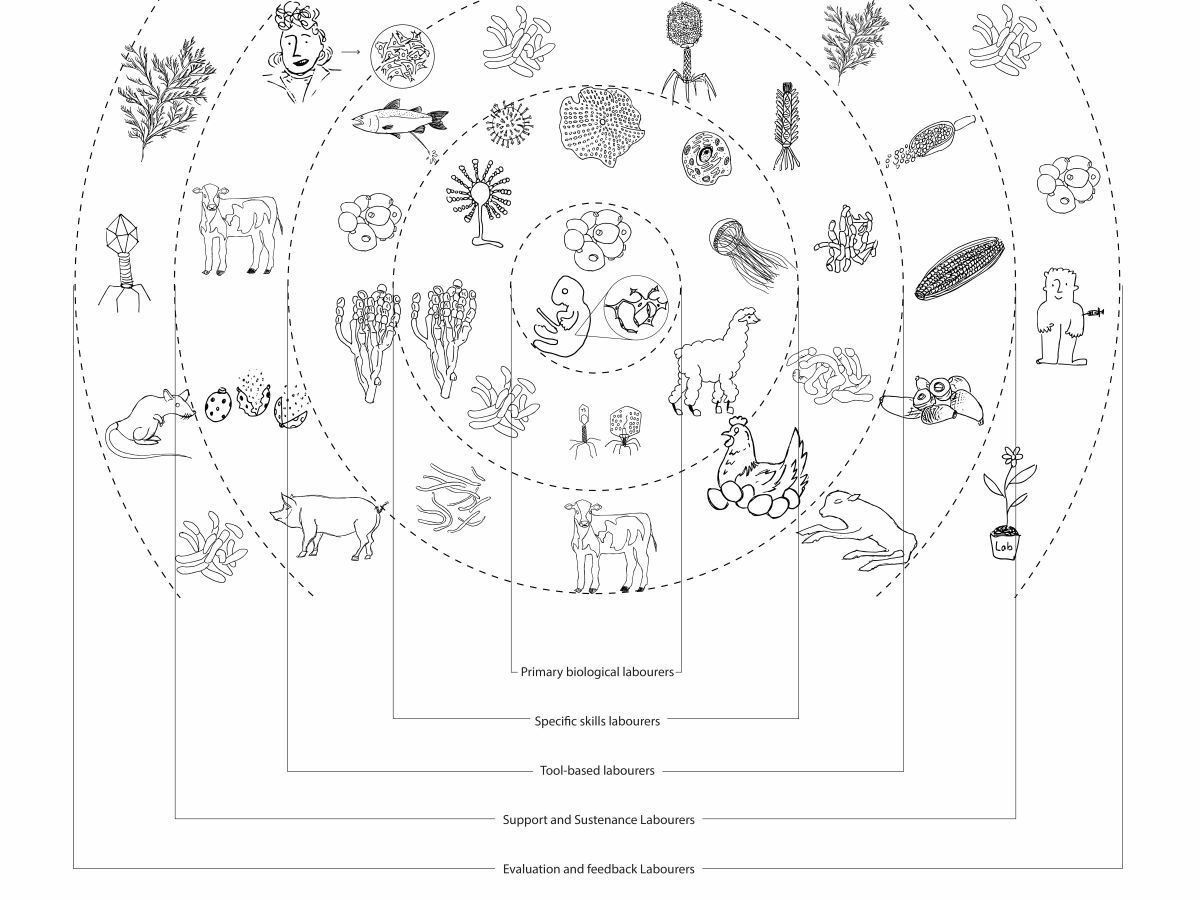

Biodesign is often framed as a more ethical, more sustainable way of working with the living. But what if the very systems that make biodesign possible rely on vast forms of labour that remain largely unseen, unnamed, and unaccounted for? In this issue, we are sharing a conversation with Yuning Chen, a biodesigner and PhD researcher in Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh, whose work asks exactly that question.

Through her Labour Provenance framework, Chen traces the hidden ecologies of organisms that sustain everyday laboratory practice, from microbes and enzymes to the infrastructures that keep them alive. In the interview below, she reflects on her path into biodesign, why labour became a critical lens for her work, and what it might mean to take more-than-human contributions seriously in biodesign practice.

Yuning Chen working in the lab (image by Y.Chen)

Can you briefly introduce your background and how you came into the intersection of HCI, design informatics, and biodesign?

My background is in environmental science and later design engineering. I started my undergraduate studies with a somewhat naive ambition to heal the world, only to be met with the disenchantment that it is often more common to develop complex technological fixes for pollution than to challenge cultures of consumerism, wastefulness, and environmental indifference. That realisation led me to take design courses as a creative way to ask different questions, not only how to solve problems, but why we create them through the ways we live, consume, and relate to the more-than-human world.

During my design masters, I was naturally drawn to working with living organisms. I was fascinated by how their agential capabilities evade control and certainty. I saw biodesign practices as a way to mediate a fairer ground for negotiation between humans and other forms of life. However, my brief experience in the biotech industry exposed a more pragmatic side. I began to notice a familiar pattern, a passion for innovation and constant newness that promises a better, more sustainable future, yet often reinscribes the same logic of extraction that caused our current crisis.

With this tension, I returned to academia. In Design Informatics and HCI, I encountered a community of researchers asking questions that resonated with my unease toward biotechnological narratives. What happens if we stop putting humans at the centre of technological design? How might technologies, infrastructures, and practices be reshaped if we take more-than-human perspectives seriously? From my perspective, the expanded field of HCI is not only about interfaces between humans and computers, but also about the cultural and political interfaces between humans, technologies, and the more-than-human world. That is where I found grounding for my critical biodesign practice.

Plant Reality Set: early biodesign work of Chen that explores human attunement to plant (image by Y.Chen)

What drew you to questions of more-than-human ecologies and labour in the first place?

Ecologies come quite naturally to me. Perhaps due to my undergraduate training, I have always tended to think of organisms in networks and assemblages. What is striking is how easily this ecological lens becomes backgrounded in laboratory and biodesign practices. In these contexts, organisms are often presented in purified monocultures, or in engineering biology, as collections of genetic Lego blocks. This creates a false sense of individuality and detachment.

Only when one looks behind the curtain, asking where enzymes, sera, or cell lines come from, where products go, who sustains the lab, and who provides nutrients for growth, does it become clear that both organisms and labs are embedded in wider ecologies. For me, this is precisely why it is important to bring an ecological lens into practices dominated by purity and decontextualisation.

Labour was a lens I first encountered through Despret and Porcher’s writing about cows. They described how interpreting organisms’ failures as resistance can reveal their active participation and labour in agricultural production. I was drawn to how labour offers an alternative way to question relationships with organisms and demand justice. Framing organisms as labouring subjects is not necessarily about intentionality, but about recognising agency in political and economic terms, extending ethical reflection into questions of structural oppression.

What motivated you to look at biodesign through the lens of labour provenance?

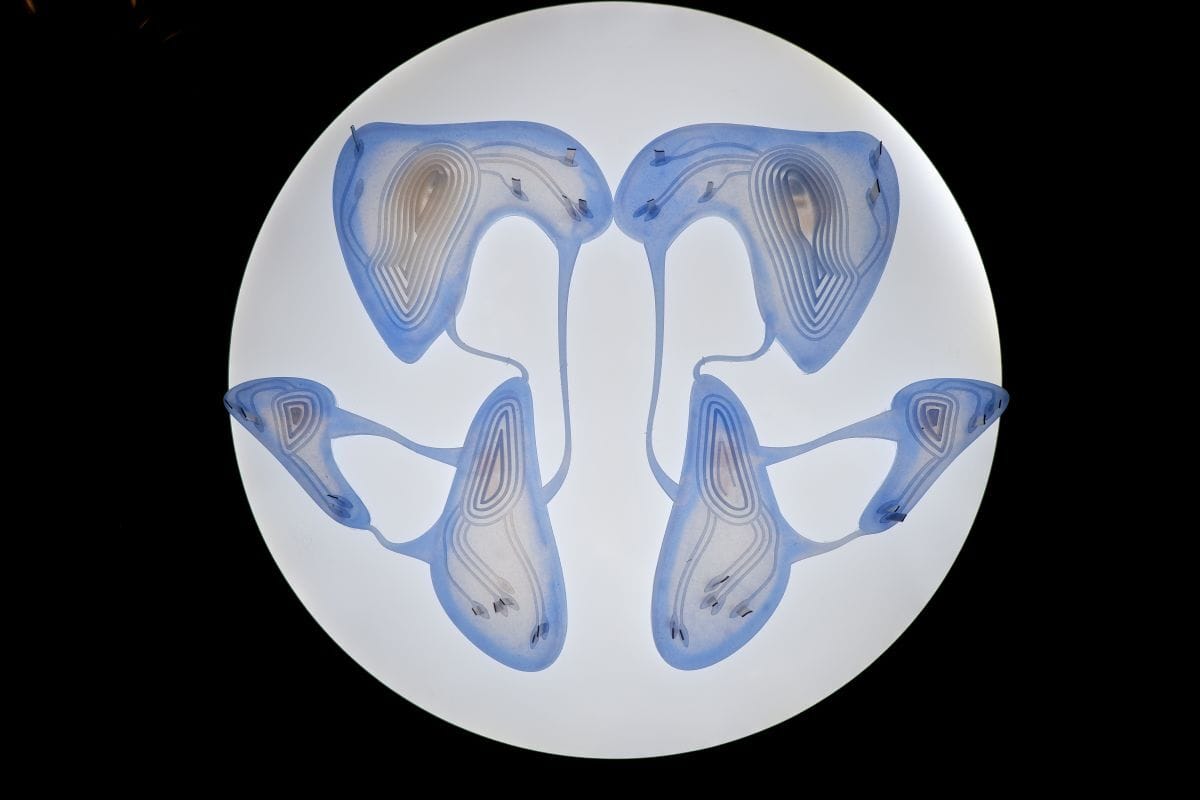

I came across the term organism agnosticism, which describes how engineering biology seeks to make living systems engineerable in ways that are agnostic to their origins. This made me curious about the abstraction of living entities from ecological and evolutionary contexts into standardised genetic blocks.

Initially, I focused on how feral organisms were transformed into homogenous chassis or blocks. Through conversations with biology colleagues, I realised that many everyday lab reagents and tools, such as enzymes and polymerases, also have organismal origins. As I investigated further, I kept discovering new clusters of living sources behind tools and materials in my own experiments.

I decided to trace the provenance of lab reagents used in a project involving common gene-editing techniques to understand the hidden ecologies sustaining daily synthetic biology lab operations. At the time, I was inspired by Wadiwel’s work on animals and capital, which analyses production systems through the lens of labour. That framework became crucial for making sense of the structural roles organisms occupy within biotechnological production, and that is how the labour provenance method emerged.

A labour provenance map (non-exhaustive) based on a biodesign experiment (image by Y.Chen)

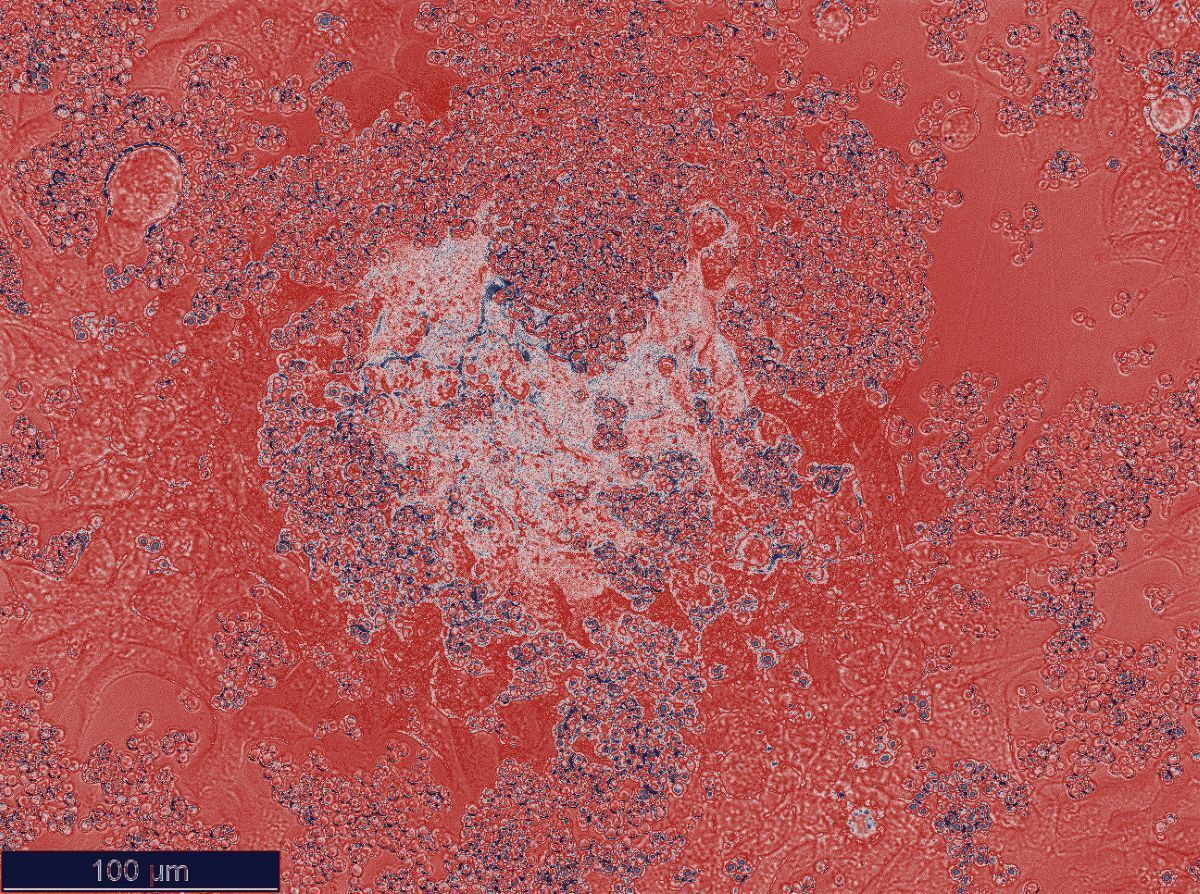

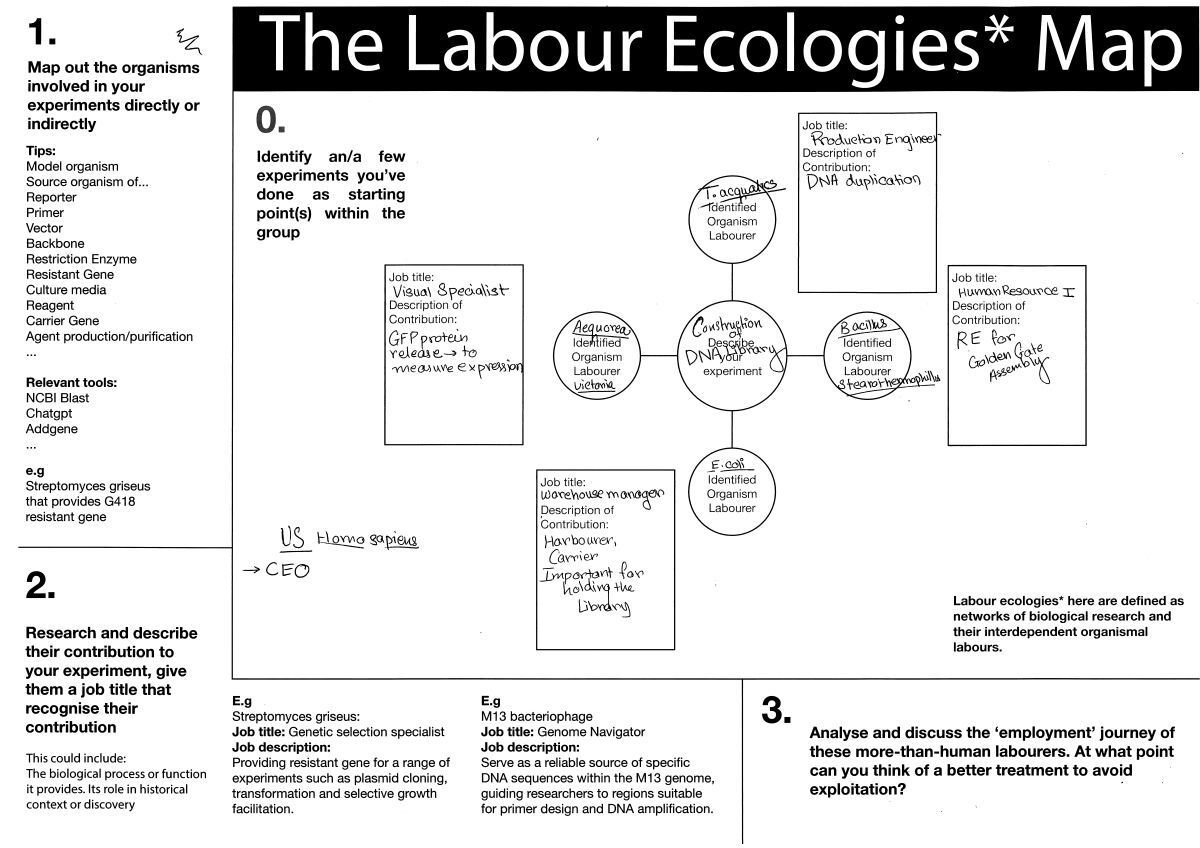

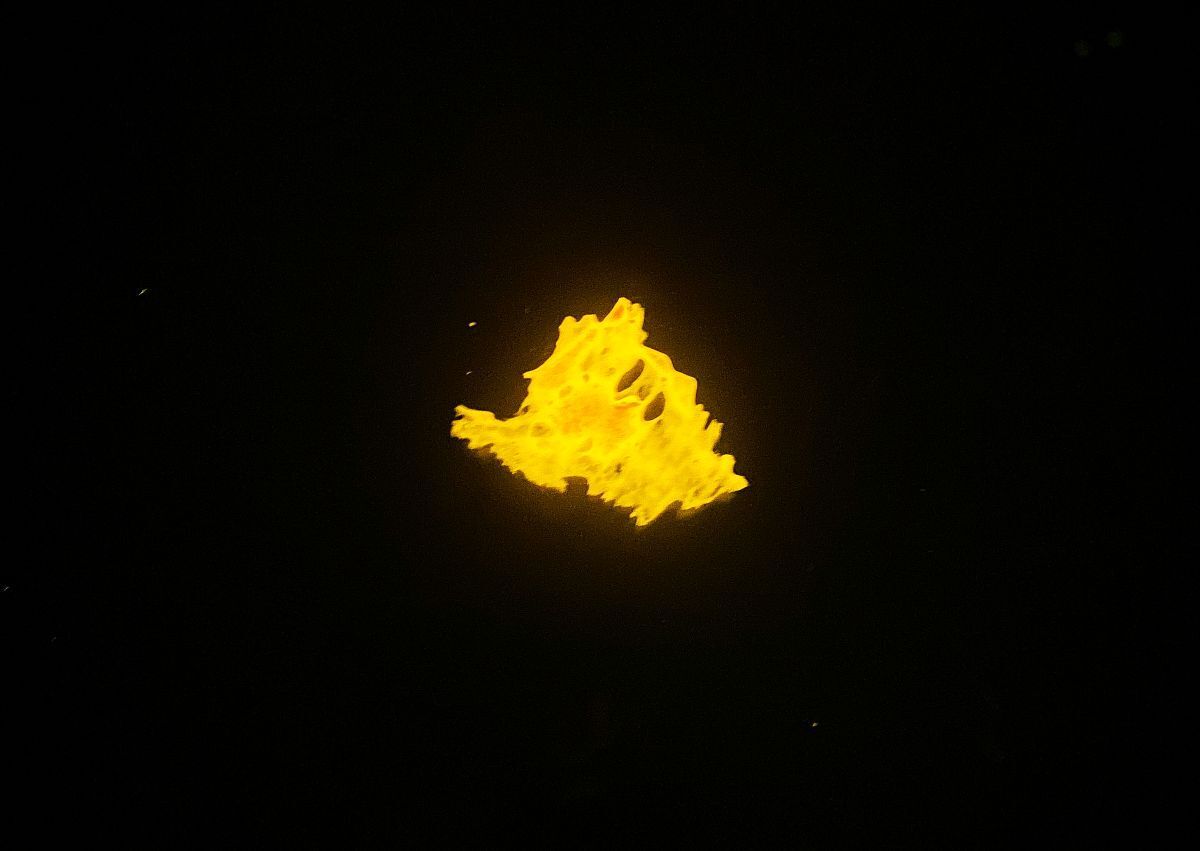

Could you walk us through the hybridisation experiment, why yeast and human cells, and what you hoped to unsettle by pairing them?

In this experiment, we use hybridisation in an expanded sense of pairing and connecting two organisms through surface adhesion, rather than fusing them into a single organism. The hybridisation of yeast and human cells, two entities with very different moral status, was intended to unsettle the boundaries of people’s moral imagination.

Yeast is a long-domesticated microbial worker and is rarely present in ethics discussions. Human cells, in contrast, are morally charged and evoke concerns about exploitation, consent, or cannibalism. Pairing them entangled these moral registers and positioned human cells as witnesses to the microbial labour that underpins daily life and scientific discovery.

Human cells were used as a tactical entry point for what Acampora calls corporal compassion, a form of compassion grounded in shared bodily vulnerability. Through this pairing, we hoped to mediate compassion toward the labour and vulnerability of other living entities in the lab.

A microscope image of yeast and HEK cell co-culture experiment (image by Y.Chen)

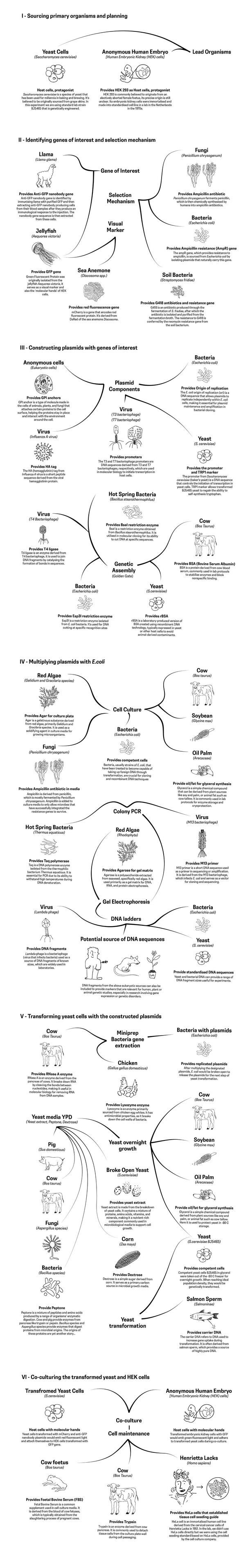

The paper identifies five types of more-than-human labourers. Which of these surprised you the most?

My level of surprise was almost inverse to the order of the five labour types, with evaluation labour being the most surprising and primary labour the least. This was less about the importance of their contribution and more about their visibility.

I began by looking into cell line histories and commonly used genes, which are primary and specific skills labourers. It was discovering the organisms behind gene-editing tools, sustenance, and even gene ladders that prompted me to ask more systematically where these abstractly named components come from.

I was surprised to find that not only tools, but also sustenance systems and evaluation mechanisms, can all be derived from living sources. This revealed how deeply laboratory operations appropriate existing ecological relations, and how quickly visibility and recognition decline from the centre to the periphery of biotech production.

The five more-than-human labourers (image by Y.Chen)

How did participants in your workshop respond to mapping organisms as workers with job titles?

Participants were generally surprised by the sheer number of organisms involved in their work, starting with main experimental organisms and gradually extending to more assistive roles. It was rewarding to see everyday reagents reframed not simply as tools, but as outcomes of living ecologies.

When assigning job titles, language played a significant role. Descriptive, playful, or metaphorical names conferred different degrees of agency and recognition. The final question about how to treat more-than-human employees better revealed a pluralistic understanding of ethical relevance. This reinforced my view that ethical sensibilities toward less emotionally relatable organisms can be rehabilitated through recognising labour and interdependence.

Sample of workshop notes (image by Y.Chen)

Where do you see the biggest blind spots in biodesign’s sustainability claims?

One of the biggest blind spots is equating biodesign directly with sustainability. This risks treating organisms as regenerative sources of functionality without considering the labour and physical pressures they are subjected to, or the wider labour ecologies that support them.

Not viewing sustainability as contingent on more-than-human labour ecologies is, for me, a significant limitation within biodesign discourse.

How do you think this framework can influence biodesign practice in labs?

I see Labour Provenance as a call to action across individual practices, tools, protocols, and institutional procurement. For individual researchers, it broadens sustainability considerations by revealing the multitude of life implicated in everyday experiments, and introduces a new ethical dimension around organismal labour and subsumption.

For research communities, it could foster cultures of appreciation and memorialisation that extend beyond primary organisms. For institutions, it could inform procurement policies by demanding transparency around the organismal sources of lab materials, which could in turn create pressure for suppliers to account for embedded labour.

Image by Y.Chen

How do you balance academic critique with practical design application?

As a practice-based researcher, I see critique and practice as co-constitutive. Without working in the lab, I would not have arrived at this perspective. Without theory, I would not have been able to contextualise and articulate it.

Practice provides the site where tensions emerge, while theory offers the lens to make them legible and consequential. My next step is to explore how these reflections can translate into relational and methodological shifts within biodesign practice.

Chen and her art exhibition showcasing part of the supply chain ecologies behind biotechnology (image by Y.Chen)

Looking ahead, what kinds of collaborations would you most like to see emerging from this work?

I would like to see collaborations that bring together biologists, designers, STS scholars, technologists, regulators, and procurement officers. The most important contribution of Labour Provenance is broadening sustainability and ethics discourse in biodesign, which requires collaboration across these different strata.

I am interested in designers working with procurement managers to visualise labour provenance, biologists collaborating with ritual designers to create memorials, and ecologists interpreting the artificial ecosystems produced by lab practices and supply chains. By revealing the entanglement of biodesign, supply chains, and multispecies labour, Labour Provenance could offer common ground for recognising shared responsibilities and acting toward more accountable forms of design with the living.

A fluorescent bread crumb from the bread made of human-yeast hybrid cells, which is part of Chen’s collaborative art project with synthetic biologists (image by Y.Chen)

This Is Where Biodesign Gets Uncomfortable

Before you close this email, it may be worth pausing on a simple question that runs quietly through this entire conversation. Who is really working in the lab? Yuning Chen’s work does not ask us to abandon biodesign or to resolve its ethical tensions neatly. Instead, it invites us to notice the layered, more-than-human labour ecologies that make biological design possible in the first place. By making these relations visible, Labour Provenance opens space for more careful, accountable, and situated ways of working with the living. As biodesign continues to grow, that shift in attention may be just as important as any new material or technique.

Thank you, Yuning for sharing your work, below are her social links if you want to check out her work further and to get in touch:

Website: https://alienyuning.net

Instagram: @alienyuning